The Memoirs of an Ancient Priest of Antinous

Transliterated and Adapted from the Original Papyrus Scrolls

By

Ernest Gill

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS BY THE TRANSLATOR

The Memoirs of an Ancient Priest of Antinous

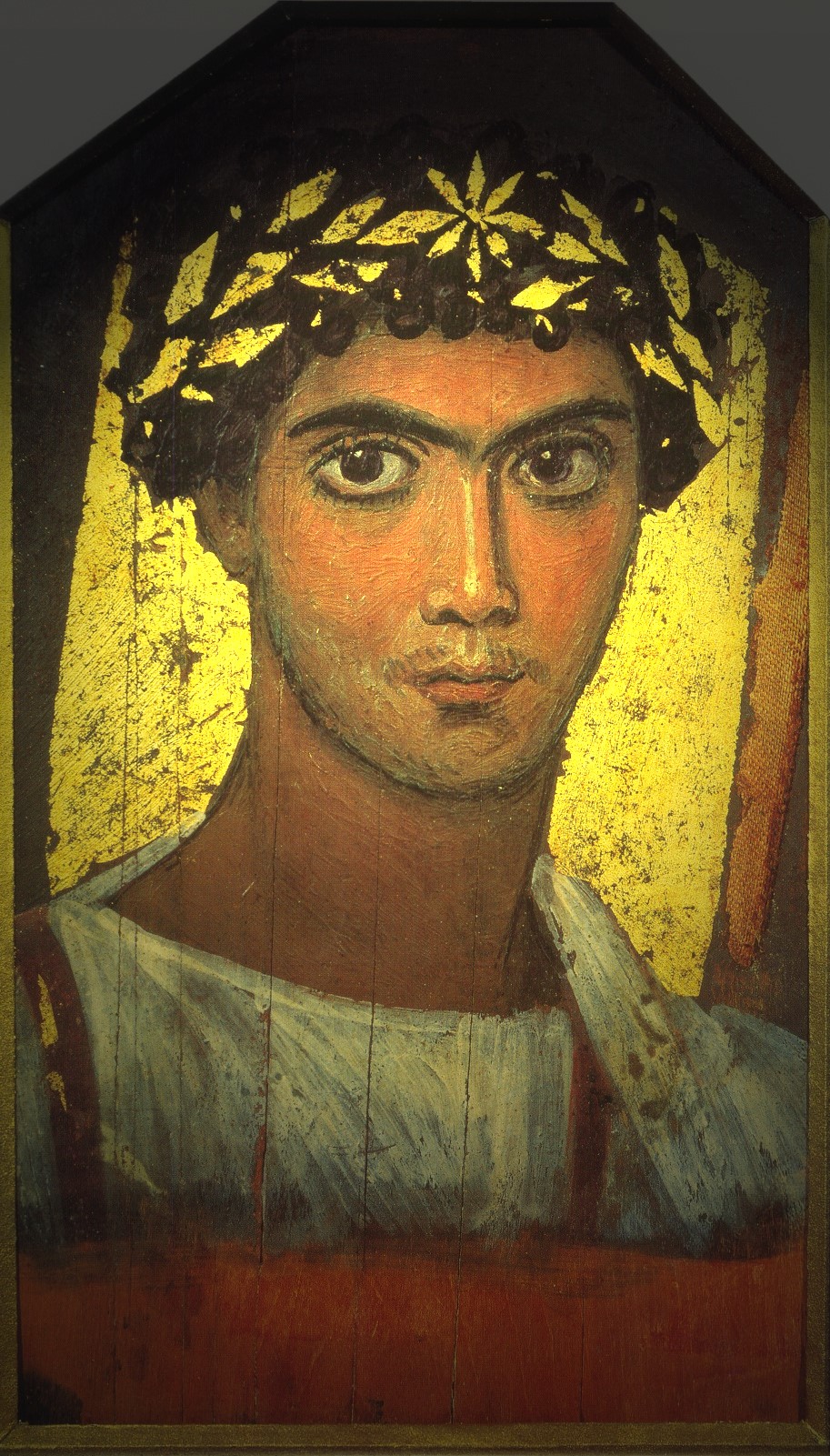

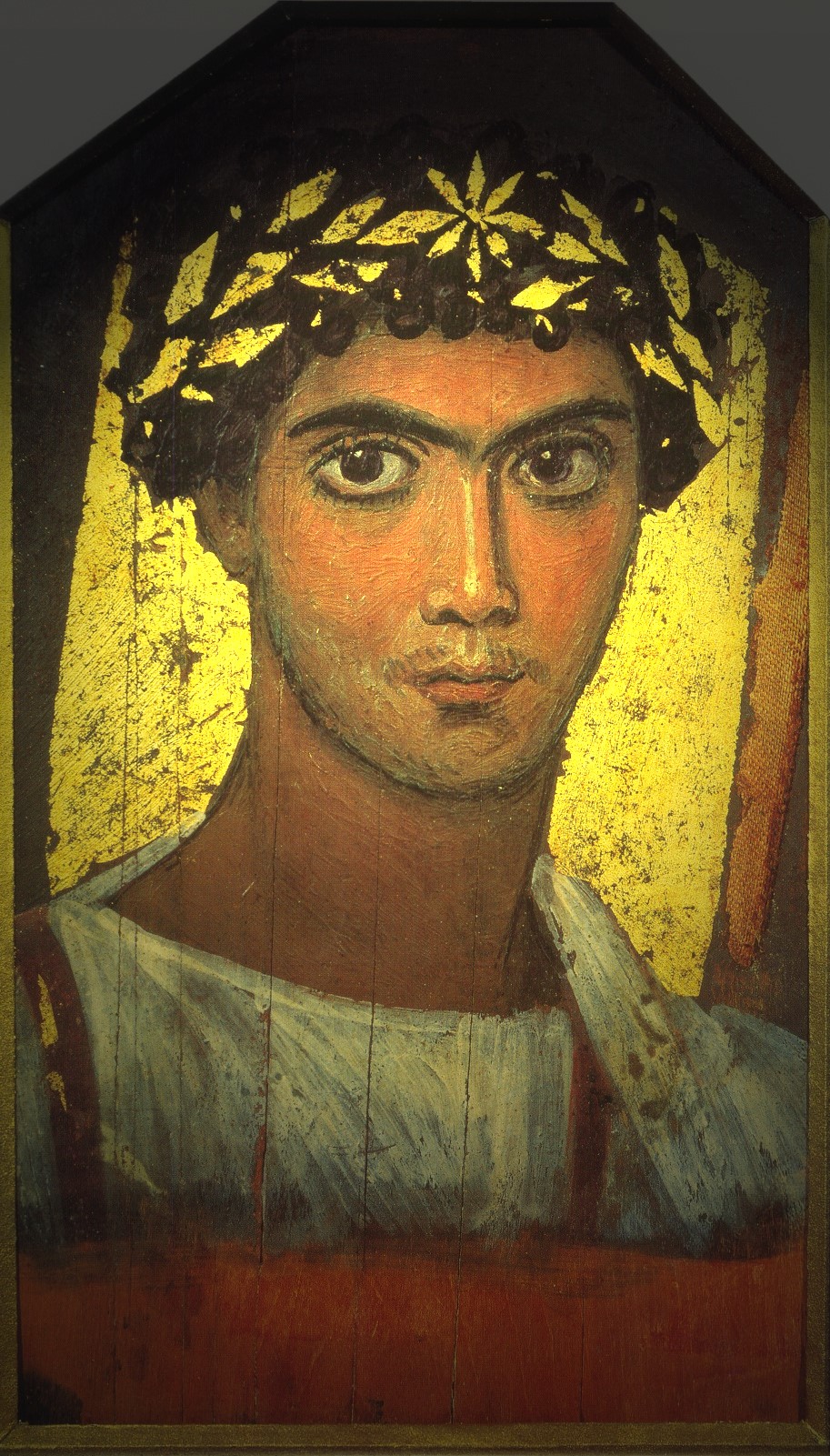

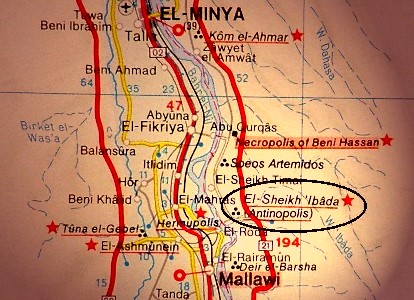

Nearly half a century ago, a team of Italian Egyptologists working at the site of ancient Antinoopolis near the modern town of Minya in Upper Egypt stumbled upon a remarkable cache of papyrus scrolls dating from the 5th Century AD. The scrolls were discovered in an underground chamber below what is believed to have been the Great Temple of Antinous, the last Classical deity prior to the accession of Christianity as state religion in the Roman Empire.

The subterranean chamber appeared to have been used as a hideaway by one of the last priests of Antinous.

Despite a collapsed roof and the ruinous state of the chamber, the Italian archaeologists discovered the fragmentary remains of a large marble sarcophagous — which was empty. Inspection of the chamber was made more difficult by an infestation of venomous and unusually agressive scorpions, the likes of which even veteran scholars had never seen in Egypt.

Broken furnishings included a table and chests containing countless amulets, small alabaster vials with remnants of unidentified oily substances, and the cache of scrolls.

It is believed one of the scrolls may have been a copy of the Memoirs of Hadrian, the emperor who founded the Religion of Antinous and established the city of Antinoopolis on the spot where the youth Antinous, the Emperor's favorite, had died in October of the year 130 AD. If so, that scroll would be the only surviving copy of those long-lost memoirs.

Other scrolls were magical texts written in a mixture of Latin, Greek, Egyptian hieratic and Hebrew "word-square" symbols, much of which were indecipherable.

All of the scrolls appeared to have been written in the same hand, perhaps by the priest who sought refuge in the chamber as Christian zealots converged on the temple. One very tattered scroll, written in a hasty hand with many mistakes, corrections and lacunae caused by vermin, seems to have been the life story of that priest himself, or perhaps of someone he held dear.

Unfortunately, the Italian team never published any of the findings. The scrolls ended up in Milan, where they perused for a time by students before a change in government in Italy brought about funding cutbacks which curtailed research. The exact whereabouts of the scrolls is unknown.

But a photostat copy of the scroll which has been dubbed "Memoiren des Antinoospriesters" (Memoirs of the Antinous Priest) was obtained by East German scholars in the 1970s. It was transcribed in part into German. But again, the collapse of Communism ended that research. In the intervening decades since German unification, museum curators painstakingly re-united ancient art which had been divided between East and West Berlin during the Cold War. Only recently have these treasures been put on view, many for the first time since the outbreak of World War II in 1939.

One of the documents which was found in an East German storage cabinet was the photostat copy of the "Memoiren des Antinoospriesters". Through a stroke of luck, we have been able to obtain a copy of those yellowing photostat pages. The text which follows is a transliteration and adaptation of a scroll not seen for more than 1,500 years.

The outer part of the scroll was eaten by insects, meaning that the opening lines are irretrievably missing. Thus, we do not know the author's name or the exact date and stated purpose of this school. The narrative begins in mid-sentence with his youth as a boy in the obscure village of Araki on the edge of the Western Desert near Nag Hammadi, 240 km (150 miles) south of Antinoopolis. Where possible, I have attempted to bridge over gaps, but much of the story is gone forever. The opening sentences have been left fragmentary, as found on the original.

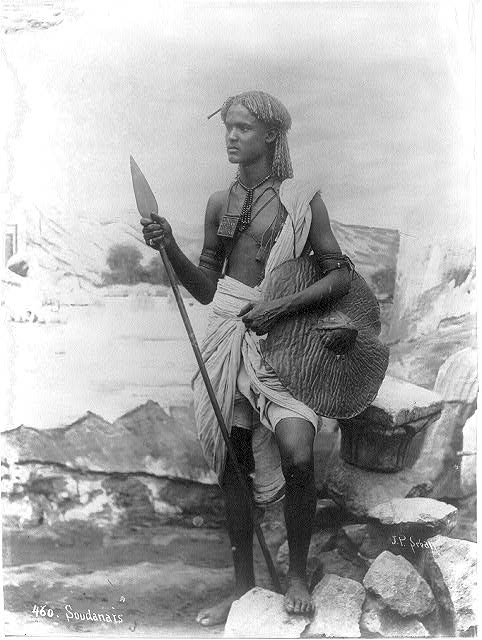

But the Gods were perverse ... only half an existence ... sought refuge among scorpions in darkness ... from the mouth of the cave high in the cliff beyond my home village called Araki ... looking south up the arroyo ... vastness of the Red Land of the Western Desert ... I saw him for the first time. A green speck against the blinding white of the desert cliffs. Walking down the arroyo, he came close enough for me to see he was not all green. His skin was black as the darkest corner of my cave. His robes were bright green like a stone I had seen once from a merchant who said it was a piece of the Nile turned to stone. I say he walked. But in fact he strode. He proceeded like our village elder on holy days.

With uncharacteristic boldness, I emerged from the mouth of the cave to stand at the lip of the precipice, shielding my eyes against the brightness. I waved and called out to him in my loudest voice, my cry echoing off the surrounding cliffs. He turned and looked in all directions, baffled by the echo, but at last seeing a ragged and very dirty little boy waving to him from the mouth of a cave high up in the cliff wall.

He climbed the trail up the cliff with the agility of a desert jackal and in no time was stood in front of me, not even short of breath. He was more than twice my height, taller than any man in our village, taller than any man I had ever seen. I could not stop gaping at his face, his green robes, the big round hat slung over his left shoulder, the mysterious bag over his right shoulder, the scary amulets dangling round his throat — I was only a desert boy, and ignorant, but I knew enough not to touch an amulet. And above all, I stared at the spear he carried in his right hand.

"Aren't you going to invite me inside to sit down in the shade?" he said in an accent which I almost did not understand. I was staring at his hair, which was braided and gathered at the back of his head like a horse's tail I had seen one time, the only time I had ever seen a horse since horses are rare in the desert. Collecting my wits, I asked him inside and was immediately ashamed of my surroundings. My few toys, made by myself out of twigs and shreds of cloth. The stone where I sat and dreamt for hours at a time.

He sat down on my stone, folding his legs under him neatly, his back stright upright, his gaze intent on me. You would never have thought he had crossed the desert on foot. With no sandals. I realized for the first time that he was barefoot. It did not occur to me at the time to ask him why he was crossing the Western Desert. People who live on the edge of the desert are accustomed to seeing oddities. And anyway, I knew that our arroyo formed part of a series of canyons which, owing to an extended bend in the Great River, constituted an overland shortcut between Thebes to the south and the great cities of the north. No, it did not occur to me to ask why he was traveling alone through the desert. But without protective footwear of any kind? Now, that was indeed curious, even for a boy who lived on the edge of the desert and whose only footwear was a pair of falling-apart sandals back in his village.

"You must be very poor not to have any shoes of any kind. Even I have a pair of sandals at home," I said, thinking of the threadbare reed sandals which I had outgrown but might come in handy as hand-me-downs for another boy.

"I never wear shoes of any kind," he said in that strange, low voice, a dry and rasping voice like the first gust that signals a sandstorm and my mother says we must batten the door to our house. "I come from a land far to the south where nobody wears shoes like you Egyptians." The way he pronounced the word "Egyptians" made me think he did not think much of Egyptians. I had never thought of myself as an Egyptian before, only as a boy from the village of Araqi. But I knew he was referring to me.

Apparently surprised himself by the rasp in his voice and aware that his throat was dry, he produced a water gourd and — after offering me a sip — took a sip himself. There was no need for either of us to explain, but we both knew that those who live on the desert never refuse a sip of water, nor take more than a sip — for one never knows what tomorrow's Rising Sun might bring in its wake, as the old saying goes.

A scorpion dropped from the cave ceiling onto his right shoulder, evincing a slight tilt of his head to the left so as to look at this creature with its raised stinger. I would have expected even a grown man to panic. A boy would have yelped and jumped up in fright. That was why I came to this cave, to escape the torments of the other village boys, who teased me mercilessly. But this man did not flinch, just looked at his shoulder as though that is where one would expect to find a venomous scorpion raising its stinger toward your neck. He raised a hand to brush it away, but I stopped him.

"Don't hurt it. Scorpions are my friends," I said, reaching out to scoop up the scorpion and place it on my own shoulder, where it crawled around my neck and down the other arm.

"I noticed you wear the sign of the scorpion goddess," he said, nodding toward my bare chest. The crudely fashioned clay scorpion on a twine around my neck was my only real possession, the symbol of Serqet, the Lady of the Scorpions.

I told him the oft-repeated tale of how I had been stung by a scorpion as a baby and how my mother had prayed to Lady Serqet and, despite the fact that everyone had expected me to die in the night, I awoke the next morning without fever and with the swelling almost gone. My mother told me that story so many times and admonished me so often never to harm a scorpion, that I grew up playing with them and letting them crawl all over me. Other children accused me of sending scorpions to crawl into their beds at night. At any rate, I was the village kherep serqetyew "Bewitcher of Scorpions" — a nickname I have retained all my life.

The stranger had a way of luring answers out of my shy mouth. Even the cave scorpions seemed to warm to him. I explained how poor we were and how my parents had too many children, the puniest of whom I was. I told how the other boys bullied me for for playing with scorpions and for being weak and not boyish enough and for walking about in a day-dreamy daze.

I told him my name and asked him his and he said, "They call me Bata," as though I would recognize that name. "You know? Bata, like Bata and Anubis in the Tale of the Two Brothers?"

I must have looked puzzled because he added, "Then I shall have to tell you the story during our journey."

I assumed he meant during our journey down to the valley since it was indeed getting late and the sun was casting long shadows and we would have to hurry while there was light. And besides, my little stomach was rumbling and I knew my mother would have onions and beanmash ready. So I asked if his journey would take him to my village of Araki and he said, "Well, it is on the way to where I am going, which is the great city of Antinoopolis, far to the north."

Again, I had not the slightest notion of what he was saying. It was only when the two of us walked into the village — he striding and me scampering to keep pace — that I began to realize he was a very special guest indeed. The neighbors scurried to the village elder, who emerged from his hut, having hurriedly put on his ceremonial beads, to meet the green-robed man on the dirt path that served as the only street in Araqi. With much bowing and scraping, the elder welcomed him as "your reverence, beloved priest of the Most Great and Good God Antinous!"

I knew the elder was very much put out by this unexpected arrival since I had heard him complain of traveling priests, calling them "parasites and moochers, only half a step above tax collectors". I could see the obvious relief on his face when the priest told him not to make a fuss because he was the guest of this small boy. The eyes of everyone in the village focused on me, and boyish snickering was audible from behind the skirts of the village fat woman. And a gasp caught everyone's attention and all eyes looked in the direction from which the gasp had come. It was my mother, standing at the doorway to our hut, with hands clasped over both cheeks. I could read her thoughts as clearly as if she were shouting, and she was near hysteria over how to provide suitable hospitality — and a proper meal — to a priest.

The green priest strode over to where she was standing, me scampering behind and the rest of the villagers following, since this would be the talk of the village for the next six months and no one wanted to miss it.

My mother, being a pious woman, had the presence of mind to bow deeply and humbly before the priest, not quite groveling in the dust, but showing obeisance I had never expected from her. The priest bent his lanky frame forward and reached out with his right hand to touch her shoulder gently. A muffled cry went up from the crowd, because it was unprecedented for a priest to deign to touch someone. Certainly, no one in our wretched village had ever been touched by a priest. Cuffed by tax collectors? Yes. Shoved aside by traveling merchants? Certainly. But gently touched on the shoulder by a priest? No one had seen that before in Araqi.

With the tips of his fingers, he pulled her to her feet and every ear in the village strained to catch his odd accent as he said very softly, "Have no fear, little mother, for great honor has come upon your home this day and the Most Great and Good God has singled out you and yours out for the highest commendation."

The look on my mother's face changed from panic to sheer horror. You must understand that there is no such thing as good tidings for people who live on the edge of the desert. There is no such thing as unalloyed joy. Joy is always mixed with grief. Good tidings are always tainted by evil sendings. The desert is like a mother scorpion. She is a good mother who carries her babies on her back. But she will also eat her babies one by one rather than let them all starve or die of thirst. She must eat some of her young in order to regurgitate their essence to feed the remaining ones.

My mother was no different. She was a good and loving mother. But she was overwhelmed by her brood of five children and a husband. She would never have admitted it, but if one child suddenly were to be taken away, her grief would be alloyed by relief. As with unalloyed joy, there is no such thing as unalloyed grief for those who live in the edge of the desert.

I now know that she must have realized what was about to transpire. She was fighting back tears when my father arrived home from the wretched fields where a few scraggly goats provided the only income for the village. She was still fighting back tears as she served chipped earthenware cups of barley beer (borrowed from a neighbor) to the priest and my father. The priest made a show of enjoying everything. He said he could eat a hippopotamus, and my father frowned at me when I couldn't help but counter, "Yes, but we only ever have onions and beanmash."

She was sobbing softly after supper when she had put my siblings to bed, all of them fighting sleep to steal glances at me and the priest seated by the fire pit outside our hut. Unlike the village elder, who had a proper house with a fire pit at the back, we only had a hole in the ground outside the one and only door. From inside the hut, I heard the sounds of my siblings whispering and my mother sobbing and my father shushing them all.

The priest and I sat under the stars and said nothing for the longest time. I thought I saw a third figure beyond the flames, but whoever it was vanished when I squinted my eyes for a closer look. One of those bully boys, I thought.

At last, after what seemed like an eternity, the priest said he had told my mother and father while I had been off to the latrine that the Most Great and Good God had chosen me to become a novice priest. He didn't say how my parents had responded except, of course, that they had had no choice but to yield to the Divine summons.

He then asked if I was prepared to go with him to the Great Sacred City to become a priest like himself.

I have often thought of that night under the stars next to the fire pit. I had nodded vigorously and said yes with no thought to anything or anyone. I had not the slightest clue. Not only did I not know what a "novice" was, I did not even know what a God was. In retrospect, that was the best pre-condition for becoming a priest. But I didn't know that at the time. In fact, the green-clad priest who was from that moment on my Mentor, said as much when he asked, or rather made the observation that, "You don't know who Antinous the God is, do you?" I think I only smiled in embarrassed ignorance. "That's good. Then we can start from scratch."

He looked up at the stars and I suddenly remembered something.

"Will you tell me the story of the two brothers during our journey to this city ... to, ah ...."

"You mean the Sacred City of Antinoopolis? Yes, of course. In fact, I'll tell you the story right now."

And so he did. And as he told me this strange story of magic and of truth and of lies and of deceit and of transformations, I was certain I saw someone sitting on the other side of the fire. It was a man with very angular features. Not anybody from our village of Araki. It was a stranger with no hair. Almost a skeleton of a man. With such penetrating eyes. He looked directly at me as the priest told me the story. And he was still looking at me as my eyelids drooped and I fell asleep with my head in the priest's lap under the stars on the edge of the desert.

As everyone knows, the twin brothers Truth and Falsehood are always at odds, so it is hardly surprising when we find them standing one fine day before the assembled Netcherew, arguing about a particularly fine and costly knife which Falsehood claims his sibling Truth has taken from him and has hidden from him, out of purest and bitterest spite. Now, whether such a knife exists, or ever has existed, is something of which even the Netcherew appear to be ignorant. But the Netcherew well know that Truth and Falsehood have done similar things to each other — and worse. So when Falsehood insists Truth has robbed him of this particularly fine and costly knife, the assembled Netcherew are naturally rather inclined to believe him.

And when Truth is unwilling or at any rate unable to produce this particularly fine and costly knife, the Netcherew suspect the twins are up to their old tricks and readily agree to give Falsehood satisfaction. And when Falsehood demands that Truth be blinded and forced to stand guard at the gateway to his house for all eternity, the Netcherew readily agree, apparently having expected (based on past quarrels) an even harsher punishment.

Some days pass (or perhaps it is centuries) and Falsehood steps out of his house and notices blinded Truth standing guard at his gate and sure enough decides the punishment for the loss of that particularly fine and costly knife (the existence of which is still unclear) was in fact too lenient. So he summons two of Truth's most loyal servants (who still serve him even as he stands blind watch at Falsehood's gate) and he instructs them:

"Take your master and remove him from my premises and lead him into the desert and feed him to the lions. Swear to me by your love of Truth that you will do this."

They swear to do this, and as they are dutifully dragging their blinded master Truth to the desert where ravenous lions lie in wait for just such occurrences, Truth baulks and tells his servants (using a very nice reflexive verb in the process, so pay attention, boy): "Drag not me myself into the desert. Instead, convey me to a pleasant oasis where I have plentiful food and water. Then return to Falsehood and tell him merely that you carried out his instructions to the letter."

When the loyal servants of Truth raise objections, their master dismisses them (and their objections) with the words: "An oath sworn to Falsehood is no binding oath."

Some days pass (or perhaps it is centuries) and Lady Passion is out for a boating excursion with her coterie when shes Truth in his oasis and observes (coining a phrase in the process) that the beauty of his body exceeds that of the earth and the firmament, indeed, of all things visible to the eye.

She desires him very much, for she sees that he is handsome in all his body. She orders her servants to take him back to her very home, where he should serve as her doorkeeper, for it is well-known that everyone who enters a portal must be examined by Truth.

He sleeps with her that very night and knows her with the knowledge of a man. And she conceives a son in that very night.

Now many days after this (some call it an eternity), she gives birth to a boy whose like has never existed in the whole of the two lands, Upper and Lower Egypt. He is tall and strong and his face is radiant and in every manner he is like the child of a God. He is sent to the school of the priests of the Most Great and Good God and learns to write very well. He practices all the arts of war, and he surpasses his older companions who are at school with him. But when his companions say to him: "Whose son are you?" he has no answer. They say, "You don't have a father!" And they revile him and mock him: "Hey, you don't have a father!"

Thusly the youth asks his mother: "What is the name of my father? I want to tell it to my companions, for they quarrel with me. 'Where is your father?' Thusly they speak; and they mock me."

Thusly his mother replies to him: "You see the blind man who sits by the door? He is your father." Thusly she speaks to him.

Then he says to her in reply: "You deserve that your family be gathered and a crocodile be summoned to make a poor meal of you."

The youth brings his father inside, makes for him sit on an armchair, places a foot rest under his feet and puts food before him. He gives him to eat, he gives him to drink. Then the youth says to his father: "Who blinded you? I will avenge you!"

Truth says to him: "My young brother blinded me." And he tells him all that has happened to him.

The Son of Truth goes off to avenge his father. He takes with him ten loaves of bread, a staff, a pair of sandals, a waterskin, and a sword. He fetches an ox of the most exceeding beautiful color. And he goes to where the herdsman of Falsehood is. He says to him: "Take for yourself these ten loaves, the staff, the waterskin, the sword and the sandals, and guard my ox for me until I return from town."

Now many days after this (or perhaps it is centuries), when his ox has spent many passings of the moon with Falsehood's herdsman, Falsehood comes to the fields to view his cattle. When he sees the ox of the youth which is exceedingly beautiful in color, he says to his herdsman: "Give me this ox, I want to eat it."

But the herdsman replies: "It is not mine. I cannot give it to you."

Then Falsehood instructs him thusly: "Look, all my cattle are in your charge. Give one of them to its owner."

When the youth hears that Falsehood has taken his ox, he comes to where the herdsman of Falsehood is and asks thusly: "Where is my ox? I do not see it among your cattle."

The herdsman lies to him thusly: "All my cattle are yours. Take one you like."

The youth shakes his head. "Is there another ox as big as my ox? If it stood on Amun's Island, the tip of its tail would lie on the papyrus marshes, while one of its horns would be on the western mountain and the other on the eastern mountain. The Great River is its resting place, and sixty calves are born to it daily."

The herdsman shakes his head in reply: "Does there exist an ox as big as you say?"

Then the youth seizes him and drags him to where Falsehood is. And he drags Falsehood to court before the assembled Netcherew. When they hear what the youth has to say, they respond: "What you say is false. We have never seen an ox as big as you say."

The youth replies to the assembled Netcherew: "Is there a dagger as big as you say? One that has Mount Yal in it for copper, in whose haft is the grove of Coptus, whose sheath consists of the Tomb of the Great and Good God, and its belt of the herds of Kal?"

And he demands of the assembled Netcherew: "Judge between Truth and Falsehood! I am the Son of Truth! I have come to avenge him!"

But Falsehood, believing his brother to be dead, takes an oath by the Most Great and Good God, saying: "As the most great and good god lives in Heaven, as the Emperor lives in Rome, if Truth be found alive, I shall be blinded in both eyes and shall be made door-keeper of the house of Truth!"

Wherupon the youth leads the assembled Netcherew to where his father is and he is indeed found to be alive.

Thus the assembled Netcherew inflict punishment upon Falsehood. He is smitten with five open wounds, blinded in both his eyes, and he is made door-keeper of the house of Truth.

Thusly goes the Story of Truth and Falsehood. Sleep well, little novice priest. Tomorrow I shall tell you the story of Anubis and his brother Bata. It is the same story as the one I have just told. With different names. And different things happen. And yet the story is the same.

As the sun rose, I opened my two eyes to discover that my head was cradled in the lap of my mother. At some point during the night, Bata my new Mentor had carried me back to the hut, where my mother could hold me one last time. Tears were in her eyes as I looked up at her. There was infinite sadness in those eyes, and yet a hint of relief.

Like the mother scorpion with the hungry babies on her back, my mother would soon have one less child to worry about. Her puniest baby scorpion would not perish, but instead would be taken to a better life. She could not possibly imagine what sort of life that might be. But it could not be worse than living on the perpetual brink of disease and starvation in Araki on the edge of the desert.

My Mentor was already packed and ready to set out. He graciously accepted a bundle of food from my mother. In return, he touched her hand and bent near to whisper something into her ear, words which no one else heard but which caused her to break down into heaving sobs and to clutch at my father standing next to her.

Next and seemingly out of no where, the priest plucked a gold coin and handed it to my father, who in that instant had become the wealthiest man in the village of Araqi. The coin, as big around as the palm of my little-boy hand and bearing the face of a beautiful youth, glinted in the sunlight. Gaping with amazement and holding it aloft, my father stood speechless as the priest clasped him by the shoulder and turned so that the two men, with my weeping mother between them, my brothers and sisters behind them, all faced the crowd of villagers. The entire village had turned out, of course, for the most important day in living memory. Holding his spear high to command attention (as if anyone's gaze would stray this morning), the tall black man spoke in the ringing, sing-song voice of a temple priest who commands respect.

"The Most Great and Good God Antinous, healer of the sick, worker of miracles, benefactor of the poor, lord of the inundation, most beautiful among the netcherew of Upper and Lower Egypt and indeed of the world, even this Beauteous Boy Antinous has singled out this village and this family to provide for him this boy child to be his priest."

All eyes were on me now.

"The bounty of the God's blessings will be bestowed upon all of you and all of your descendants and your livestock. The village of Araki will become immortalized in the Hall of Records of the Great Temple as a place of piety and magic. Mages will come here in distant centuries from distant lands, seeking wisdom and solace. Your descendants will welcome them as you have welcomed me, for this is a Sacred Place."

My father, who had looked so large to me before, now looked miserably tiny next to this giant of a man in green robes. Increasing his grip on my father's shoulders, the priest went on, "This family is blessed above all others in this village. Honor them and treat them with respect. The Most Great and Good God will be watching."

Then he motioned for everyone to kneel and went into a chant as he passed amongst the crowd, extending his hands in blessing — but pointedly touching no one. He had touched my mother and my father. That would be remembered by everyone in the village as long as they lived.

And then it was time to leave. The village elder presented me with a new pair of reed sandals. His wife gave me a decent linen kilt to wear (I could tell it pained her to part with such a prize). The priest took the kilt from me and folded it into his voluminous bag, telling the woman her generosity would be repaid by the Most Great and Good God. And as I slipped on the stiff new sandals, I realized for the first time that I was actually leaving the only place on Earth that I had ever known. Some other child would get my battered old sandals. I would never return to my cave to fetch my pitiful toys made from scraps. I would surely never see my family again. I did not know much, but I knew that the world is a vast place, and people from Araki never had the luxury of traveling to distant cities, except to be tried for tax evasion or cattle theft, in which case they never returned to report on what wonders they had seen. The scorpions would miss me and I them. But I assumed (rightly as it turned out) that there would be scorpions in Antinoopolis.

My mother embraced me and smeared my face with tears. My brothers and sisters hugged me but I could tell they were scheming over who might get which of my paltry possessions. They would not get my clay scorpion charm. That was around my neck.

The village people — men, women and those bratty bullies who had never uttered a kind word to me before — they looked at me in awe and wonderment. And then, like a flock of birds changing course as one in the sky, the crowd parted as the priest strode forward, with me stumbling along behind in my stiff new sandals which squeaked with every step and which would soon rub blisters on my feet.

And we were off. One striding with dignity. One trippingly following as if the Ka of his right foot did not know where the brother Ka of his left foot was going.

Once we were beyond the village and over a low ridge, he turned to me to ask which way was the best path down to the Great River. Having never seen the river, I had no idea. But he allowed as though it did not matter since the Great River was only a short distance away. And indeed, within an hour we had left the desert plateau and were walking through lush irrigated orchards. He said it was only another hour or so to the Great River, and there we would turn left and follow the flow of the Nile downstream to Hermopolis, ancient Sacred City of Hermanubis/Thoth. He knew someone there. And from Hermopolis, we would cross the Nile to Antinoopolis. It would take many days, he said, but that was good since there was much to do before I could enter the gates of the Great Temple.

He looked at me long and hard as he said this, but I was paying little attention to his words, being more interested in the canopy of fruit trees arching over my head like the curved ceiling of the Araki village elder's house. And watching enormously large and enormously loud-buzzing flies — which I later learned were bees. There are no bees in the desert. So vast is the difference the Great River makes. One moment you are stumbling over desert rocks. The next moment you are strolling through irrigated orchards full of wondrous creatures called bees. Little wonder that the hieroglyph for "kingship" is a bee.

But my reverie was cut short when my Mentor pulled me off the pathway sharply towards an irrigation ditch.

"But first we're going to get you cleaned up, young man. I couldn't offend your mother by pointing out how filthy you are. But I cannot go another step until you are taken care of." The way he pronounced "taken care of" sounded ominous to my young ears. He had put down his bag and other gear and had stripped off his garments and his amulets and was already wading into the water. There was not a hair on his body, unlike grown men in Araki who were as woolly as goats. Looking at me still standing on the shore, he shook his head and said, "No, no. You are a disgrace. It would be unseemly for a priest of my rank and stature to be seen traveling with you. Now strip off and get in this water."

I had little enough in the way of clothing to remove. A once-white loin cloth so soiled that it was nearly black. My new sandals. Removing them and carefully placing them well away from the water, I stood at the torrent's edge, tentative.

"Come on, boy. Or haven't you ever bathed before?" And realizing I hadn't, he took a big sloshing step toward me and yanked me into the water. I thrashed and yelped, gulping water and knowing I was about to drown. But his strong arms held me securely at all times. He had retrieved some strange knife-like utensils from his copious bag, along with some foul-smelling powder which created a lather. He seemed to be scraping the very skin off my bones and I yelled and thrashed all the more. But it was no use. His grip never loosened.

And just when I thought it was all over and was heading toward the shore, he pulled me back to him and said, "Oh no you don't. Not until I've shaved your head. You are crawling with lice. I picked them out of my robes all morning after you laid your head on my lap last night."

Before I had time to scream, he was already going to work with the most wicked-looking, razor-sharp Nubian flint knife. And within minutes my scalp was bare — revealing a mass of oozing sores and scabs from lice bites.

Muttering something in his native tongue, interspersed with Egyptian words such as "deplorable state" and "utter disgrace", he drew me ashore and told me to "just stand there and don't move until the sun has dried you thoroughly". Looking down at my naked body, I was shocked to see how utterly pale I was. I had always thought of myself as being brown-skinned, but now realized it had been caked-on dirt. In fact, my skin was pinkish white, red in places where he had scrubbed particularly hard.

From the seemingly bottomless depths of his bag he produced an unguent jar and proceeded to massage a pleasant-smelling and quite soothing ointment onto my scalp. Then he stepped back and, clicking his tongue, said, "The sun will burn you to a crisp before we even reach the Great River."

Peering into his bag again, he reached inside and pulled out a long sheaf of green fabric and proceeded to gather it around me and pin it into place.

"Do all priests wear green?" I asked.

"No, not all," he said through clinched lips holding pins. "The different schools wear different colors — red, yellow, blue. And of course priests from temples for other Gods dress entirely differently from us." Wiggling his lips to shift a pin, he said out of the corner of his mouth, "Entirely different. We Antinous Priests are distinctive. And you and I belong to the only brotherhood of priests who wear green."

He was finished pinning me together into a garment which covered most of the bare flesh of my arms and legs, making me look for all the world like a caterpillar.

He waggled his head from side to side as if to say, "It will have to do," and then said aloud, "But of course you're not supposed to be wearing the green yet. You aren't even a properly inducted novice yet. But by the time we reach Hermopolis your skin will have become accustomed to the light of day instead of the blackness of a cliff cave ... I hope ... and we can find something appropriate at my friend Su's house."

He stood up and suddenly noticed the top of my head. The salve had soaked into my irritated scalp, but it was far too sensitive to be exposed to a bad sunburn.

Kneeling at the edge of the irrigation ditch, he scooped up mud and clay and created a poultice which he then troweled onto my head like a brick-layer applying mortar. I could not see what he was doing, but it felt pleasantly cool. He seemed to be taking great care molding it and forming it.

"There," he said at last, wiping the poultice from his fingers. "That will do fine. Your scalp will heal and you won't get a sunburn. Here, have a look for yourself."

From the eternal reaches of that bag he drew out the most extraordinary thing I had ever seen. It was like the fine pan that the village elder's wife uses to cook with — the envy of all the other women in the village. But this was no pan. Its burnished surface gleamed like the sun. I looked at it and saw a pink-faced boy with a brown cap looking back at me. It was the first time I had ever seen my reflection, my proper reflection. He held it so that I could look at myself from all sides. He had applied the poultice so that it looked like a skull cap.

I was delighted at the discovery of my own image, the discovery of myself as I truly appeared without a layer of grime. I started babbling excitedly. It was a moment of unalloyed joy. One corner of Bata's mouth turned upwards into what was the approximation of a smile for him. It was one of the few times I ever saw him smile.

I told him how the only time I had ever seen my reflection in the past was when I looked into a bowl of water. And to demonstrate, I leaned over the water of the irrigation ditch — and drew back in shock. A tiny baby bird had fallen from its nest in the branches overhead and had drowned in the water, its featherless, lifeless body floating on the water.

I scooped it up with both hands and held it to my mouth, trying to blow life back into it. But it was too late. It was a tiny, pinkish-naked version of myself. And it was dead before it had even begun to live. Tears filled my eyes and I couldn't see.

From somewhere in the distance, I heard a sound which I had never heard before. It was a squeal which turned into a high-pitched, wailing scream which did not seem to stop. It was as a scream loud enough to alert the gods themselves that something awful had happened on Earth. Only when I was forced to catch my breath to inhale did I realize the scream had come from me. My brief moment of unalloyed joy had turned to unalloyed grief — as is always the case with those of us who have lived on the edge of the desert.

Still holding the bird, I looked up at Bata, but could not see him clearly. I saw a double image. He was standing there. But looking over his left shoulder I seemed to see another man — the same angular and almost skeletal man I had seen through the flames under the stars the night before. I blinked my eyes to clear the tears, and the man was gone. Only my Mentor was there, looking at me with a quizzical expression on his face.

"I knew you were special, but I had no idea ...." he said, his voice trailing off. Without explanation, he cupped his two hands over mine holding the dead bird, and he said, "You have summoned Hermanubis to guide this soul across the waters. Now close your eyes while I do the rest." And he chanted and rocked back and forth, making me rock in time with him.

I do not know how long that lasted. Not very long, I suppose. But when he told me to open my eyes, I felt better and my sobbing had subsided and my tears had left dry trails of salt down my cheeks. Guiding my hands, he gently placed the bird in the water and gave it a little push to "send it on its way".

He used a clean cloth to dry my face and blow my nose. Then we packed everything back into his bottomless bag and got back on the path through the irrigated orchards down to the Great River.

Out in the sunlight again, he gave me a once-over glance to make sure no delicate flesh was exposed to the sun.

"You look like a mudpie with that poultice on your head," he said affectionately, and my lingering sobs turned to a giggle. "That's what I shall call you from now on." Then raising his voice to the ringing, chanting, priestly voice he had used back in the village, he sang out, "Come along, little mudpie. We have along journey ahead of us, you and I, before we reach the Sacred City of the Most Great and Good God."

As we walked down the green path towards the Great River — a tall, black man with green robes and bare feet; and a very small, pinky-white boy with green robes and squeaky new reed sandals — the morning sun was directly in front of us to the East. I have often thought of the events of that morning so very long ago, when unalloyed joy and unalloyed grief cemented the bond between my young self and the green-robed priest who would love me all his life and who would be forced to endure the unendurable because of the heartless vanity of my dark heart. How could he have known that I would be the last novice priest? After me there would be no others. Darkness would fall like the night falls over the desert — sudden and unannounced and cold and black.

But that darkness was still far off in the distant future on that bright morning as we headed into the morning sunshine. That was the irony which intrigues me now — we were heading into the morning sunshine, and yet we were living in the sunset of the world.